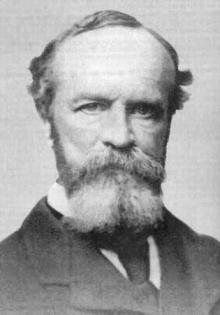

William James

Rin’dzin Pamo recently pointed out to me one of the most salient (and irritating) features of pop spirituality: its smugness.

“Spiritual but not religious” folks often have a hipster attitude: we’re cool because we get it. People reject the new paradigm just because they are too dull to get it. They are stuck in the old, bad way of thinking, which we saw through ages ago.

It might be helpful to know that the “new” paradigm isn’t; and that hipsters had the same smug attitude about it a hundred years ago.

The new smugness—same as the old smugness

Current “spirituality” is a recycled version of monist philosophy from two hundred years ago. Its core idea is that “all is One,” or “we are all part of God,” or “everything is totally connected.” In other words, the unity of all things is the key spiritual fact.

The psychologist-philosopher William James helped kill that one off a hundred years ago. I’ve just noticed that in one of his critiques, dated 1907, he writes:

When a young man first conceives the notion that the whole world forms one great fact, with all its parts moving abreast, as it were, and interlocked, he feels as if he were enjoying a great insight, and looks superciliously on all who still fall short of this sublime conception.1

This is the same smugness that we see among the SBNR crowd today. (Nowadays it is as—or more—likely to be a young woman than a young man who has this attitude, though.)

What’s to be smug about?

A sense of superiority is essential in every subculture. Different subcultures see themselves as superior in different ways, though, which helps form the emotional “texture” of the subculture. I’ve been trying to figure out what’s distinctive about the smugness of monist spirituality. I don’t think I’ve quite got it yet—which is why this is a blog post, not a book chapter. Maybe a reader can nail it, in the comments?

I think it must have to do with monism’s distinctive approach to knowledge and justification. Monism rejects reason and evidence. (It has to, because reason and evidence lead rapidly to the conclusion that it is wrong.)

We all have some ear for this monistic music: it elevates and reassures. We all have at least the germ of mysticism in us. And when our idealists recite their arguments for the Absolute… I cannot help suspecting that the palpable weak places in the intellectual reasonings they use are protected from their own criticism by a mystical feeling that, logic or no logic, absolute Oneness must somehow at any cost be true… This mystical germ wakes up in us on hearing the monistic utterances, acknowledges their authority, and assigns to intellectual considerations a secondary place.2

Monism justifies itself through non-conceptual insight, intuition, emotional experience, the moment of transcendent realization. Now, many people seem not to have this insight. In fact, they think monist spirituality is silly and the “insight” is emotional self-deception and wishful thinking.

The monist response is that people have varying levels of “spiritual development.” It takes a special capacity to understand that everything is perfectly connected and that you are manifestation of God. Spiritual capacity may be in-born, or can be developed by spiritual practice, and it makes you a special person. Obviously, those who get it are on a higher plane of development than people who are stuck in the old materialist paradigm.

So what is the insight, anyway?

William James continues:

Taken thus abstractly as it first comes to one, the monistic insight is so vague as hardly to seem worth defending intellectually. Yet probably everyone in this audience in some way cherishes it. A certain abstract monism, a certain emotional response to the character of oneness, as if it were a feature of the world not coordinate with its manyness, but vastly more excellent and eminent, is so prevalent in educated circles that we might almost call it a part of philosophic common sense.

This is rapidly becoming true again, in the “LOHAS segment” of “upscale and well-educated” people.

What’s queer about it is that there is so little to it. As James observed, it is “so vague as hardly to seem worth defending intellectually.” It is a stance, not a system; an emotional attitude, not a coherent idea:

‘The world is One!’… why is ‘one’ more excellent than ‘forty-three,’ or than ‘two million and ten’? In this first vague conviction of the world’s unity, there is so little to take hold of that we hardly know what we mean by it.

The difficulty in debunking monism is that it is so insubstantial that you have to do monists’ work for them. You have to put together the case for monism yourself—the case that monists would have to make if they wanted to support it. (They don’t have to do that, because people adopt monism mainly because it seems the only alternative to dualism and nihilism, which are obviously wrong.)

The only way to get forward with our notion is to treat it pragmatically. Granting the oneness to exist, what facts will be different in consequence? What will the unity be known-as? The world is one—yes, but how one? What is the practical value of the oneness for us?

Asking such questions, we pass from the vague to the definite, from the abstract to the concrete. Many distinct ways in which oneness predicated of the universe might make a difference, come to view.

James goes on to lay out various things “all is One” might be supposed to mean, and then points out what’s wrong with each.

I’ll be doing the same thing, although my taxonomy is different, and aimed at current spiritual trends, rather than 19th century academic philosophy.

It’s all about God

Monism became popular in Europe in the 19th century. God was not yet dead, but he was having alarming falling spells, memory lapses, and bouts of demented rage. The clueful recognized these as early symptoms of the spongiform encephalopathy that eventually killed him.

A personal God with specific characteristics was no longer attractive. And yet, many people feel they cannot do without the emotional functions of God. The monist solution is to invent an abstract God, which serves many of the same purposes, but which is immune to criticism based on specifics. This God might not even be called God—it is called “the One” or “the Absolute” or “cosmic consciousness” or whatever—to clearly separate it from the discredited Christian God.

There is no doubt whatever that this ultra-monistic way of thinking means a great deal to many minds. “One Life, One Truth, One Love, One Principle, One Good, One God”… But if we try to realize intellectually what we can possibly mean by such a glut of oneness we [realize] it always means one KNOWER…

“Spiritual but not religious” really means “I believe that there must be Something that will save me from death, details, alienation, and finitude. I don’t believe in a God separate from me, because it couldn’t save me from those things.”

There is a real insight there. I’m not sure it’s something to be smug about, though.

- 1.This is in Lecture IV of his Pragmatism, “The One and the Many.”

- 2.This and all the other quotes are from the same chapter of James’ Pragmatism.