Bright lights can chase away the winter blahs. You may need a lot of light—more than you can get with ordinary bulbs, or with a “light therapy lamp.” Here’s practical ways to make your space feel like a summer day when it’s dark outside.

It’s five p.m. in late November now. It’s been a gloomy day, and it is completely dark outside. I am working in a room with very bright lights spaced evenly around its periphery. It looks and feels like a sunny May afternoon in here. I feel great, and I will write productively until 8 p.m. Before I discovered sufficiently bright lights, I would be miserable and useless at this time.

This is the second of two web pages about bright light supplementation for improved winter mood and productivity. The first page, YOU NEED MORE LUX, explained how and why bright light works, and how to make it work for you. It also explains why most lights sold to treat seasonal affective disorder probably won’t work for you: they are no brighter than a single regular household lightbulb.

This page explains how to get actually bright light, in practical terms. Currently, that is possible only using industrial lighting solutions, typically used for lighting warehouses, parking lots, and football stadiums.

The first half of the page, “Ways to get much more light,” begins with inexpensive options that require no effort to set up. You can just order them off the internet and put them on your desk. Then it discusses better, brighter options that cost more. In some cases, these require basic tool use to install.

The second half, “What to look for when shopping for light supplements,” explains how to choose. LED lighting technology has improved rapidly over the past several years and probably will continue to. The first half links some specific products as a convenience for readers. (Amazon sends me a couple dollars per day in return, via their Associates program.) I haven’t done detailed comparisons, and anyway those may not be available next year. The second half explains what features make LEDs suitable for winter light supplementation. These will probably not change soon.

Brief disclaimers

This page assumes that you have been inspired by the previous one to experiment with brighter light than is provided by standard light therapy lamps. As that page said, there is currently no scientific evidence that this will work. So, nothing here should be taken as medical advice; proceed at your own risk. That said, summer sunlight is still brighter than you are likely to be able to achieve artificially, and presumably sunlight does not cause you trouble. Still, I’ll point out a couple of particular possible risks. First, even standard SAD light therapy can trigger hypomania or mania. If you know you are prone to either, consult a mental health professional first. Second, consult an ophthalmologist if you have, or are at risk for, any eye conditions such as macular degeneration.

Since this is experimental, I encourage you to report your experiences in the comment section of this page. We’ve had many lively discussions there, over a decade. (This page has changed radically over that time, as I’ve repeatedly revised it for new lighting technologies, so some earlier comments may lack context.)

Ways to get much more light

Inexpensive, nearly zero effort starter solutions

The most important thing is to do something. If it’s already past the equinox and the winter blues have set in, it may be hard to do anything. Light deprivation makes everything seem too complicated, and too much of an effort.

So I’ll suggest a couple things you can do that are simple, minimal effort, inexpensive, and will probably work. These are not the best things. They may not be enough for you. They’re probably enough to see that very bright light can make a significant difference. Once you have experienced that, you may be motivated to put more effort and money into more powerful alternatives. Or, if you are already persuaded, you can skip ahead to those.

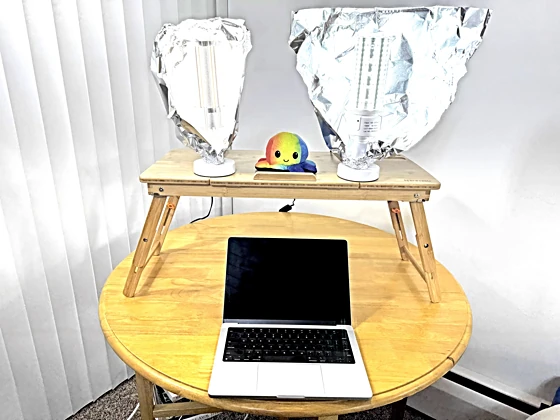

The simplest thing is to get a couple of daylight white 100 watt LED panels and put them on your desk. If you put these on either side of your laptop, you’ll know what actually bright indoor light means—something you have probably never experienced. Two together are roughly equivalent to 2000 watts of incandescent bulbs.

I don’t have 100W ones, but here is a 200W one to give a sense:

It’s not turned on, because when it is, it blinds the camera, and you can’t see anything in the photo!

You can get two of these at $60 for the pair (or actually $40 right now, for 2025 Black Friday). I haven’t tried that brand, but they have 3000 reviews on Amazon averaging 4.6/5, so they’re probably fine. (The last part of this post provides advice on how to shop for LED lights. Some criteria are not obvious!)

LED panels produce quite a lot of heat. The 200W ones I have are not too hot to put on most surfaces; I can’t speak for this other brand. I also have 600W ones that definitely are too hot, so I put them on heat-resistant trivets ($9 for two).

100W ones should be reasonably close to you—eighteen inches to two feet from your eyes. Try one on either side of your workspace. If you can, put them above eye level, on some sort of stand. Do not look directly at them; let the light enter your peripheral vision as you look at your book or screen.

An alternative is a pair of daylight white 100W LED “corn bulbs.” There are many brands of these available on Amazon and elsewhere; I got several of these ($37 currently). They have been fine, but similar ones are now less expensive and better rated. For example, these are currently $48 for a pair. You can put them in any regular lamp that’s rated for 100W or more, if they fit. They are much bigger than a regular bulb; I put mine in this lamp base, which costs $22 for a pair, meaning a total cost around $70 for the complete lamp set.

You will probably find that using either panels or corn bulbs makes you markedly more cheerful and productive! This may take effect rapidly, possibly even within minutes of first use, although the usual story is that you need to use a light therapy light for a couple weeks to get relief. (Maybe that’s because they are badly underpowered?)

As I said, this is not an ideal solution. One reason is that you will probably find them unpleasantly glare-y. (I’ll explain how to avoid this, with more effort and cost, later in this post.)

They do need to be too bright to look at—like the sun, which they’re simulating. This is not the way we’re used to relating to indoor lamps. Once you get used to it, very bright light is extremely comforting in winter.

I have found the glare, when in peripheral vision, mildly unpleasant. It’s tolerable though, and definitely worth it for the mood-lifting and productivity-enhancing supplement effect. If you don’t mind a bit of craft work, you could rig “diffusers” to cut the glare and spread the light out. There’s special cloth for this purpose used by photographers, or you could try a sheet of translucent plastic. But there are better solutions!

More light in your peripheral vision

You will probably find that lighting up a small area, leaving the rest of the room comparatively dark, feels unnatural. That’s clear in the photo above. The shadows around your little pool of brightness may come to seem slightly creepy.

You will probably soon realize that having bright light just in one place is not as much as you want, and the idea of having your whole room evenly bright, without glare, becomes excitingly attractive. That’s what the rest of my recommendations are about.

The photo below is what the same scene shown above looks like when it is completely dark outside but the room is lit with 1200 watts of additional LEDs spread around its periphery. Much more inviting, isn’t it? The little 100W LEDs are not necessary at all, although they are turned on just as brightly in this photo as in the previous one.

A couple 100W lights are enough to be effective, but only if you keep them quite close. I suggest that lighting up an entire room is much more pleasant. It means you can move about, there aren’t dark corners, and the light is diffused and can come from above, which is much more natural-feeling.

Lighting up a room that brightly will cost you a few hundred dollars, which might seem like a lot for light bulbs, but it is totally worth it if it makes you cheerful and productive in the winter—as it did for me.

High powered LED panels: brightest, best cost/watt, may require some DIY

Higher-powered flat LED panels are used for overhead lighting in warehouses, parking lots, and stadiums. As of 2025, they go up to 1000W, so one or two can make a room plenty bright. They are less expensive than corn bulbs for their light output, and since all of it gets directed forward, none is wasted. If you can install them without too much hassle, this is currently the best approach to bright light supplementation.

Panels come in different shapes for different purposes, and pose different mounting issues.

Warehouses use “UFO high bay” lights:

- these are about half as expensive per watt (or light output) as corn bulbs

- as of 2025, they go up to 600W, for about $100

- they are available either with a hook to hang by a chain, like a chandelier; or with a mounting bracket that you’d screw to the ceiling

- some are dimmable, unlike other industrial light formats

I hung one of these over my work station in November 2025:

It cost $60 when I ordered it a couple weeks ago. It’s mysteriously unavailable at posting time, but there are lots of similar ones available! I wrote a little more about this over on my Substack.

In a different format, I have been using this brand of 600W stadium light every winter starting in 2020. Here is one on top of a tall bookshelf, well above eye level:

I’ve used these heavily for years and they have been trouble-free. One is enough to make a small home office bright enough for me. We now have three times that wattage in a larger room.

These lights come with a mounting bracket, which I originally screwed onto an exposed wooden ceiling beam. That was quick and easy. Then I moved to a different place where I couldn’t drill into the ceiling. I mounted it in a wire shelving unit I got at Home Depot:1

On top of a bookshelf, if you have one in a good place, is much easier.

Generally, high-wattage LEDs are all roughly equally efficient, so comparing watts is nearly equivalent to comparing light output. A 600W panel puts out just about six times as much light as a 100W one.

The price of that particular product has been stable since 2020, a bit over $200, while LEDs generally get brighter and less expensive every year. This newer 600W one is currently $83; and this 1000W one is a bit less than $200. I haven’t tried either.

Bigger corn bulbs

Corn bulbs have several advantages:

-

They screw into regular light sockets, so you can use them in a variety of ordinary lamps.

-

You can add a few lamps at a time until you find you have enough. For me, 1200W is about right for a typical bedroom, which can be accomplished by spreading four 300W bulbs around the room. Your light sensitivity or brightness preference may differ.

-

You can turn on just one or two of them to get a lower light level. Almost no industrial lighting is dimmable, so turning on and off individual lights is the next best thing.

Relative to LED panels, corn bulbs have some disadvantages:

- More expensive per amount of light emitted

- Since you’ll probably want several for a room, they add clutter

- They send light in all directions equally; some may be wasted

High powered corn bulbs are much larger than ordinary bulbs, so you can use them in some ordinary lamps, but you need to be sure there’s room. They’re also somewhat heavy, so you want to choose lamps that won’t tip over. They won’t fit inside typical lamp shades, and also produce a fair amount of heat, which might be a fire hazard, so you will probably want to remove the shade from whatever lamp you use.

Corn bulbs above 100W also usually have a bigger screw base than regular household bulbs. Regular household bulbs and lamp sockets are size “E26” in the US and other places that use 110V electricity; they are size E27 in Europe and other places that use 220V electricity. The larger ones are E39 (also called “Mogul”) in the US, and E40 (“Goliath”) in Europe. An inexpensive adapter lets you use a big E39 or E40 bulb in a normal E26 or E27 socket. This is safe so long as the socket is rated for at least as many watts as the bulb.

Another easy way to use corn bulbs is to hang them from a rail, wall bracket, or the ceiling. A “hanging lantern cord” has a socket at one end, a plug at the other, and often a switch in the middle. Here’s a 100W corn bulb in an E26 lantern cord and a 240W one in an E39 lantern cord. For an E39 bulb, you could also use the adapter and an E26 cord, but the E39 cord has a hanging bracket that takes extra weight.

I’ve bought several different brands of corn bulbs, and they’ve all been fine. This 400W one is about $80 in 2025; I haven’t tried that brand, though. The brands I suggested in 2023 have been discontinued, so I don’t have a specific recommendation now.

What to look for when shopping for light supplements

Specific LED product recommendations become obsolete rapidly, because what’s available keeps changing—for the better each year. So this half of the post explains criteria for choosing. These guidelines should hold true for years to come.

Brightness: lumens, watts, and “equivalent watts”

My overall theory is that more light is better, and specifically that much more light than SAD therapy lamps provide is much better than a therapy lamp. So getting enough light for as little expense and hassle possible is the first criterion. What kind of light you get also matters a lot, and we’ll consider that after this.

Lumens are the unit of measure of how bright a lamp itself is—how much light it produces. Lux are a measure of how much light you get. These are not the same; the further you are from a lamp, the less light you get. Converting one measure to the other is not straightforward; it depends on how close you are, and how much of the light is directed toward you (vs. away in other directions) .

To light the whole of a medium-sized room, brightly enough for me, takes about 100,000 lumens. This is based just on experience, not any theoretical calculation. Since people seem to differ in how much light they need, what is right for me may be more, or less, than what’s right for you.

I haven’t measured it, but I think the 100,000 lumens probably provides less than 10,000 lux in my office. (10,000 lux is the recommended dose for SAD treatment.) However, for me, lighting a whole room this way seems significantly more effective than 10,000 lux from a single light, such as a “therapy lamp.” I suspect this is due to the peripheral vision effect I discussed earlier. The daylight sensing cells are spread over the whole retina, so illuminating your whole visual field, even with somewhat less light, works better than concentrating somewhat more light in one corner.

It is probably easier to think about LED power in watts than in lumens. All LEDs are about equally efficient in how many lumens they produce per watt; it’s roughly 100 lm/watt. (“lm” is the abbreviation for lumens.) More powerful LED lights are somewhat more efficient in how much electricity they consume per lumen. They’re also generally less expensive to buy per lumen, or watt.

Household LED bulbs output about 70 lm/watt, versus typical industrial lights at about 100 lm/watt. Some high-watt bulbs and panels claim as much as 160 lm/watt. I’m somewhat skeptical of this, although still higher efficiencies have been shown possible in the laboratory.

Unfortunately, many products do lie about how bright they are, or how many watts they draw. There’s many credible Amazon reviews that say “this product was dimmer than I expected, so I measured it, and they exaggerated the output by 50%.” I’ve avoided such products, but when buying you have to just accept some risk of this, because there’s no independent testing. Manufacturers with an established reputation may be less likely to lie; and if a product is dramatically cheaper than similarly-rated ones, it may be more likely fraudulent.

Throughout my discussion, I’ve taken advertised specifications at face value, because there’s currently no alternative.

Also, watch out for “equivalent watts.” LEDs are often sold in terms of how bright they are compared with some other sort of bulb. For example, in a hardware store, you’ll see household LED bulbs sold as “75W” that are approximately as bright as an old fashioned 75W incandescent bulb. In fine print, the package says that’s “75W equivalent,” and it’s actually a 12W LED. A 75W LED is reasonably bright; a 12W LED is… as bright as a 75W incandescent, which is to say quite dim. High-wattage industrial lights are, similarly, often labeled with watt equivalents of the earlier industrial lighting technologies (HID, HPS, MH, CFL) they replace.

Color temperature is critical; you want about 5600K

Simplifying somewhat, “color temperature” tells you how much blue there is the light. This is critical, because only blue light triggers the system your body uses to tell that it’s daytime. (I explained that here.) You want plenty of blue light during your simulated daytime of 12+ hours, which keeps you alert and engaged. You want to avoid blue light past your simulated sundown, around seven or eight p.m. for me. Blue light after that tells your body it’s still daytime, which messes up your circadian rhythm and makes it hard to sleep. (More about that here.)

Color temperature is measured in K.2 Actual daylight is 5600K. “Daylight white” bulbs are between 5000K and 6000K, and that’s what you want; it has the right amount of blue.3 Sometimes “cool white” means that too; sometimes it means more than 6000K, which will work, but may look unnaturally blue.

“Warm white” (3000K) is probably not effective for preventing winter blahs, and “neutral white” (4000K) is probably significantly less effective than daylight white.

You should use normal, non-bright residential warm white bulbs for your regular house lighting, and switch to those at your artificial dusk time.

Color quality may matter; I don’t know

White light, you may recall, is a mixture of all colors. However, quite different amounts of different colors can add up to “white.” For example, “white” could include much less blue-green light than daylight if there’s more blue and more green—and typical LEDs do exactly that. This matters if you are an artist, because blue-green paint will look duller under LED light than under daylight.

It may also matter because the daylight-sensing cells in your retina are most sensitive to sky-blue light, which is somewhat greenish, and less sensitive to deep, royal blue light, which typical white LEDs produce more of than daylight.

Higher quality LEDs produce ratios of individual hues closer to daylight than typical LEDs do, and that may make them better for bright light supplementation.

Color quality is usually specified as “CRI,” the Color Rendering Index, which goes up to 100. Most white LEDs are rated 80 CRI. “High CRI” is a meaningless marketing term that can mean anything upwards from 80. 90 CRI corn bulbs are not much more expensive than 80 CRI, but are much less different than the numbers would suggest.4 Genuinely high CRI is 95 or more.5

Bulbs in the 95+ CRI range are much more expensive; several times the price of ordinary LEDs of the same brightness. On the other hand, maybe the better quality means you don’t need as many lumens.

I haven’t experimented with these, due to the cost. Some friends say the light feels better, and is worth paying for. Whether it would make enough of a difference for me, or for you, I don’t know.

If you want brighter high-CRI light, professional video production lights are currently the way to go. These have several significant advantages:

- you can get them extremely bright in a compact package

- they’re available in moderately high (95) to very high (99) CRI

- they mount on a photographic tripod, so there’s no DIY required

The disadvantage is that they are much more expensive per watt than lower-CRI corn bulbs or panels. However, prices are falling for these, as with all LEDs, and you may find them affordable now, or in the near future.

GODOX and Aputure are well-regarded professional brands. In 2023, my casual Amazon search turned up this one, which is 190W, 5600K, CRI 96, for $175. Nick Cammarata on twitter recommends this one, which is 1200W, tuneable color temperature, and CRI 96. It costs almost $3500, which is sadly out of my price range. (By the way, if you would rather avoid Amazon, you can buy video lights at B&H Photo, a highly reputable supplier to photographic professionals.)

High CRI, although pleasant, may not be optimal for supplementation. Maybe light with more sky blue in it than natural sunlight would be more effective at a given brightness level. There’s been one clinical test of this, which found that sky-blue enhanced LEDs did work better than standard ones (yay!), but the effect size was quite small (oh).6

There is a commercial product based on this hypothesis, the Chroma Sky Portal. I know people who use and recommend it. I don’t know of any testing of its effectiveness versus equivalently bright standard LEDs, which are much less expensive.

Aesthetics

No industrial light is going to go well with your home decor (unless you are into the industrial look, in which case, wow, get some UFOs!). No light made for home use is bright enough (for me).

This may change; I’m certainly not the only one who wants genuinely bright home lighting. I won’t be surprised if, in ten or twenty years, it’s normal to have 100,000 lumens pre-installed in the ceilings of the living rooms of newly-built houses.

Flicker

Some people find LED flickering bothersome. I can’t see it. (My spouse can, but isn’t bothered by it.) The amount of flicker apparently varies between lights, but it’s not specified, so I don’t know how you could choose low-flicker ones.

Durability/reliability

Amazon reviews often complain that an LED light failed soon after purchase. I’ve had this happen this only once (out of about twenty high-wattage lights I’ve bought). It was a panel that was dramatically less expensive than alternatives. I don’t know of any way to avoid this (other than reading reviews, which are not always reliable themselves).

- 1.Jess Reidel came up with the same solution independently!

- 2.K here is for kelvin, which is a unit of temperature. Rather confusingly, “cool white” light has a high color temperature, and “warm white” light has a low color temperature. This is because of some physics that is interesting but not relevant here.

- 3.Color temperature is not a perfect measure of how well a light stimulates your eye’s daylight detectors. Two bulbs with the same color temperature may contain somewhat different amounts of the necessary wavelengths. For a summary of relevant research research, see for example Allison Thayer’s “Industry must move beyond CCT to articulate circadian metrics.” (CCT is “correlated color temperature.”)

- 4.There’s a useful interactive visualizer at https://www.waveformlighting.com/high-cri-led; scroll down to the “Compare our spectral power distribution” section and try pushing the daylight, 99 CRI, 80 CRI, and 90 CRI buttons there.

- 5.CRI is not a great measure, especially at the high end. There are several alternative measures; you may see “TLCI,” the television lighting consistency index.

- 6.Eo et al., “Development and Verification of a 480 nm Blue Light Enhanced/Reduced Human-Centric LED for Light-Induced Melatonin Concentration Control.”