I mean, OK, but what even is it?

Lots of people wonder whether cosmic meaning exists, or are bitterly certain there is none, or try to figure out how to find it—like, should I try meditation or something? Or they regret that we’ve collectively lost it, and say we need to return to it—but what are they even talking about?

Sometimes “cosmic meaning” refers vaguely to the unspecified, special kind of meaning that, if it existed, could deliver on the promises of eternalism. Usually, though, “cosmic meaning” seems to mean something a bit more specific.

But what? What makes a meaning cosmic or not? No one complaining about the lack explains, and they give no examples, so I don’t think they have a clear idea of it. Theologians supply explanations of “eternal meaning,” but rarely discuss “cosmic meaning,” and treat them as equivalent when they do. All the philosophical treatments I’ve found are worse than useless, due to a mistaken idea of what “cosmic” means.

This page details several common, half-thought ideas about “cosmicness.” A better understanding explains why you might reasonably feel distraught that it’s missing in your life, and practical approaches to addressing the problem.

But first: although nobody tells you what cosmic meaning would be, you’ve probably heard many times how they know there isn’t any. It goes like this:

The sales pitch

Caught up in the trivial concerns of your everyday life, you never stop to ask if any of it is truly meaningful. If you step back from your subjective illusions of meaning for a moment, you can see that everything you do is just schemes generated by your animal instincts for survival, with no point beyond that.

Zoom out from your self a notch. Some people think their friends and family give their lives meaning, but—if you even have any—none of them know or care about some of the things you are most stressed and obsessed with. Most of your thoughts and memories and pains and disappointments will remain forever private. You are fundamentally alone.

Zoom out again. The community you live in is full of people who don’t know you at all. If you get run over by a mattress truck while crossing the street and die horribly, they won’t hear about it, and if they do, they won’t care. You might as well not exist.

Zoom out. You live in a country of millions of people, run by idiot politicians and greedy billionaires who care for nothing but power and money. If everyone in your neighborhood died because some corporation spilled toxic waste in the water supply, it would be in the news for a week, and then everyone outside would forget about it and nothing would change.

Zoom out. You are stuck on a rock with eight billion people for whom your life is completely pointless. Perhaps you hope to gain some fame, to achieve something great, hoping that might give your life some actual purpose. Well, suppose you succeed and everyone on earth knows your name and reveres your accomplishments. So what? In the vastness of the cosmos, the whole earth is a miniscule grain of dust, coated in a thin layer of organic chemical scum. Some bacteria glommed together in colonies a few billion years ago and eventually turned into monkeys. Now some overgrown bacterial colonies in the middle of nowhere are deluded into thinking they are significant.

Zoom out. The 1990 “Pale Blue Dot” photograph shows Earth through a telescope on the Voyager 1 spacecraft, from just under four billion miles away, a distance of forty times that of the Earth from the Sun. The Earth takes up 0.12 pixels of the image. Carl Sagan wrote:

Look again at that dot. That’s here. That’s home. That’s us. On it everyone you love, everyone you know, everyone you ever heard of, every human being who ever was, lived out their lives. The aggregate of our joy and suffering, thousands of confident religions, ideologies, and economic doctrines, every hunter and forager, every hero and coward, every creator and destroyer of civilization, every king and peasant, every young couple in love, every mother and father, hopeful child, inventor and explorer, every teacher of morals, every corrupt politician, every “superstar,” every “supreme leader,” every saint and sinner in the history of our species lived there--on a mote of dust suspended in a sunbeam.

The Earth is a very small stage in a vast cosmic arena. Think of the rivers of blood spilled by all those generals and emperors so that, in glory and triumph, they could become the momentary masters of a fraction of a dot. Think of the endless cruelties visited by the inhabitants of one corner of this pixel on the scarcely distinguishable inhabitants of some other corner, how frequent their misunderstandings, how eager they are to kill one another, how fervent their hatreds.

Our posturings, our imagined self-importance, the delusion that we have some privileged position in the Universe, are challenged by this point of pale light. Our planet is a lonely speck in the great enveloping cosmic dark. In our obscurity, in all this vastness, there is no hint that help will come from elsewhere to save us from ourselves.

Zoom out. In the big picture, nothing that happens on Earth makes any difference at all. The next nearest star to the Earth after the Sun is Proxima Centauri. It is almost three hundred thousand times as far from Earth as the Sun: thirty trillion miles away. If Voyager 1 was headed there, it would take seventy six thousand years to arrive. Proxima Centauri has an Earth-like planet that is barely detectable with the most powerful telescopes. Nothing we can do will have any impact there. If it is inhabited, do you think the aliens there care anything about your vain ambitions, constant worries, and rapidly approaching death?

Zoom out. Both stars are located nowhere in particular in the Milky Way galaxy, which is fifty thousand times farther across than the distance between them. The galaxy contains hundreds of billions of stars. The Milky Way is one galaxy among many in the Local Group, whose largest is the Andromeda Galaxy, roughly a million times further from us than Proxima Centauri. The Local Group is part of the Laniakea Supercluster of a hundred thousand galaxies, which is a part of a galaxy filament, which is a tiny thread within the cosmic web of the universe.

Between stars, there is only empty space: silent and cold and dark and unimaginably lonely.

If there is life in the Andromeda Galaxy, it may be incomprehensibly more powerful than humanity. Alien civilizations have had billions of years to develop. Standing before them, they seem god-like to you; but to them, you are as utterly insignificant as bacteria. If they noticed you, it would be with momentary, implacable hostility before recycling your body’s atoms to make paperclips. Their reign and achievements stretch across billions of stars, and their eldritch technologies and worlds-destroying wars are utterly alien and incomprehensible in terms of human values. Yet viewed from the perspective of the universe as a whole, they too are revealed to be impotent, pointless, useless, meaningless: sound and fury, signifying nothing.

Stand on a frozen rock that drifts endlessly alone in the Andromeda Galaxy, a shard of a planet whose star system was blown up in some cosmic battle that was already forgotten a billion years ago, and realize exactly how “meaningful” your momentary microscopic life on Earth is.

An illusory perspective

I hope you are feeling a little lonely, frightened, and depressed now—or at least can imagine how other readers might. That will help understand our several different upcoming analyses of what’s going on in that sales pitch. It combines a number of sleazy rhetorical tricks.

A first analysis: this sales pitch is similar to the one in “No eternal meaning,” which transported you, in your imagination, to the miserable meaningless end of time. This one transports you to a miserable meaningless rock squintillions of miles from nowhere, and dumps you there.

It’s the same trick, getting you to visualize something that is misleading and not in your interest. “In the big picture,” it says: but, it’s a picture, a fiction, not a concrete reality. If you imagine looking at things from a standpoint where, you are told, they look like X, then they will look like X in your imagination. If you stand behind a translucent red screen, everything will look red. Why would you choose to do that? You can also imagine “looking” at your life from another galaxy… but you are just making things up, guided by a voice that wants to throw you into despair.

As you pull away, an object appears to dwindle in size, but this is an illusion. Things don’t actually get smaller when you move away from them, and they don’t get less meaningful either.

Meaning depends on contexts and purposes. If you go to a place with no context and no purpose, there will be no meaning there, at least not until you’ve hung out for a while. But if you could teleport to a nice Italian restaurant in the Andromeda Galaxy for lunch, and return to Earth in time for your regular afternoon tryst with a coworker in the office broom closet, your life here would not look less meaningful when considered from your table at Osteria Andromeda.

The sales pitch tries to suggest that the perspective from extremely far away is somehow more accurate than looking at your life close up. It’s true that stepping back can sometimes give you a more objective view, which may be more accurate in some ways. It’s not true that accuracy of perception increases without limit as you get further and further away.

Maybe that’s given plausibility by the idea that God is infinitely far away—outside the universe entirely—but sees everything in it perfectly clearly. You, however, cannot do that, and cannot realistically imagine it. And anyway, God apparently regards at least some of what we do as highly meaningful, despite His great distance.

Thought soup

Most philosophy papers about cosmic meaning argue about whether you should buy the sales pitch: do galaxies make everything meaningless, or not?1 None of that is relevant, because no one except a few astro-geeks cares about galaxies. Obviously it’s true that galaxies themselves are meaningless, but it’s super unclear how that’s supposed to make your life meaningless.

The philosophers missed the point, because they assumed that “the cosmos” and “the universe” are the same thing. It turns out those are critically dissimilar, and the cosmos hasn’t got any galaxies in it. More about that later.

Fortunately, we aren’t doing philosophy here. We’re figuring out how to get out of a pattern of thinking, feeling, and acting that makes us miserable and useless. So our job is to figure out what makes that pattern seem sensible and attractive anyway.

Nihilism doesn’t make any sense rationally, but it’s important to sort out the underlying irrational thoughts and emotions, for two reasons. First, to counter them on their own terms. Merely ridiculing irrationality may not have the power to exorcise it. Second, investigating specific irrational ideas reveals broader patterns of more and less accurate and functional relationships with meaningness.

Persistent irrational ideas are often vestigial remnants of ancient understandings. Some were once mainstream theories, but discredited centuries ago; some pre-date civilization, and even humankind. They survive as “thought soup”: fragments of evolutionary history and long-dead ideologies that persist in popular culture as ways of talking and thinking and feeling and acting: clichés, metaphors, plot points and story arcs.

“Cosmic meaning” and “not cosmically meaningful” are such. Where did they come from?

Same old story

Dateline: Southern France, 31,000 BC.

When you were fourteen, your parents were killed and eaten by a pack of giant hyenas. The clan chief heard screaming and arrived with some other men in time to drive them away and rescue you. A hyena had bitten a chunk off your right calf, leaving you permanently lame.

When your leg had healed enough that you could hobble, the clan’s shaman took you aside one night and spent hours pointing at the sky and telling you tales of the buffalo woman whose spurting milk formed a bright band across the night, and the hunting of the Great Bear that leapt into the stars, and the adventures of the wandering planets, and the secret trails shamans walk among the constellations. You nodded and tried to follow along, but none of it made sense and the stars looked pretty much like stars, same as they’d always looked. He said he would take you on as an apprentice, since you’d never make it as a warrior or hunter, but first you’d have to pass the Ordeal in the Cave Of The Beasts. The monsters in the cave were terrifying, the absolute blackness was terrifying, and it was freezing and you were starving, and you failed.

The chief had little use for you, but he slowed the clan’s hunting ground migrations so you could keep up, and made sure you got enough of the hunters’ kills not to starve. He found a place for you scraping hides and sharpening spears for other men to use.

The clan was ambushed by warriors from some strange tribe. They yelled “bar bar bar” at each other and had no human speech. They had magic sticks that hurled sharpened willow wands into men’s bodies. Your chief ordered a charge, and the men ran in with their spears. The strangers turned as if to flee—but then turned again and waved their magic sticks and everyone fell screaming in pain. The chief had a willow shaft in his eye. He died the next day, along with most of the rest of the warriors.

His nephew, not much older than you, became the new chief. He had always had contempt for you. He told the clan that they were to sharpen their own spears, and scraping hides was women’s work. Now the clan members mostly would not look at you when you tried to talk to them, and no one would tell you why. You could tell that they were preparing for next migration, although the moon was still far from full.

You woke one morning and the camp site was empty. The clan had packed silently and left before dawn, without you. You yelled but there was no answer, and you expected none. Which way had they gone? The camp site was on the plain, at the foot of a high rock formation, a pile of boulders the clan used as a lookout point. Climbing it was slow with your bad leg.

At the top, you looked out across the vast empty plain in every direction, but you could not see the clan. They must have set off long before dawn.

You remembered men coming down from the lookout saying that they had spotted smoke from the cooking fires of other clans. That seemed the only hope: to wait until your clan made camp and built a fire, and then to try to cross the empty plain alone to reach them and beg to be taken back in. You waited all day, looking out in every direction, but there was no smoke.

Night fell. You had no fire—that was the shaman’s job—and no food. It was freezing cold and dark and you were utterly alone. There was no moon, and the stars shone in meaningless pitiless indifference.

In the dark, there were giant merciless monsters.

Insignificance

I hope you noticed that this story is significantly similar to the nihilist sales pitch. We’ll explore the parallels which make nihilism emotionally effective. Its rhetoric tries to make you feel lonely, worthless, and vulnerable.

Here’s a clue to the meaning of “cosmic meaning.” Whereas discussions of “eternal meaning” display anxiety about the nebulosity of ethics and the meaning of death, discussions of “cosmic meaning” display anxiety about the nebulosity of purpose and about personal significance—or, actually, insignificance. The nihilist sales pitch drives toward the “realization” that you are utterly insignificant “when viewed from the perspective of the universe as a whole.”

Well, yes. Significance is not an intrinsic property; it is a relationship. Something is significant only to somebody. It is true that the Andromeda Galaxy does not care about you. So what? You don’t care about it, either, unless you are an astro-geek.

Humans are obligatorily social animals. Before we killed off all the cave lions, an isolated human in Southern France was a snack. A band of humans with spears could usually intimidate predators into leaving them alone.

Being part of something bigger than yourself—a protective clan, at minimum—is essential to human survival, and the human way of being, and of relating to meaningness. Partly this pre-dates humanity; chimpanzees have similar social structures, as presumably did our common ancestors millions of years ago. It’s likely that our overgrown brains developed mainly to understand and exploit social relationships.

Especially critical is maintaining your social role within the clan. That is the basis of social significance: you are valued enough that the clan chief will risk his life, and his warriors’, to save you from cave hyenas. You are valued enough that the chief gives a meaningful purpose to your life, even if it is only sharpening spears and scraping hides.

When you lose that purpose, when you lose your social significance, then the clan abandons you—and then you are alone in the night, and will die of cold, hunger, or predation within hours or days. That pitiless evolutionary selection pressure underlies our contemporary craving for purpose and significance. (Or that’s my story, anyway. I don’t have specific evidence for it.)

The “No cosmic meaning” hypnotic induction tries to regress you into this archaic part of your brain which is terrified of being abandoned in the dark. In part, it puts the universe in the place of your clan, as the greater whole of which you are a part, and tells you that this cosmos is utterly indifferent to you, or even actively hostile. Cowering before the clan council/galaxies, you have no value, no significance, no purpose, and so no protection, support, or comfort.

The universe

In current usage, “the cosmos” means the same thing as “the universe,” but it used to mean something entirely different. “Cosmic meaning” concerns the cosmos, not the universe. Philosophers’ confusions largely stem from failure to recognize this.

Taking “cosmos” to mean “universe”, one might guess that cosmic meaning is to eternal meaning as space is to time. That is, cosmic meanings are those that apply uniformly throughout the universe. However, “cosmic meaning” is rarely if ever used that way. That would be “universal meaning,” which we’ll deal with elsewhere.

Some philosophers think cosmic meaning is about “the universe as a whole.” This makes no sense. First, “the universe” isn’t a thing, and there is no whole. There’s an extremely large amount of empty space with—comparatively speaking—an extremely small number of atoms scattered around randomly. Occasionally a few of them glom together to make a galaxy or something. This is obviously meaningless, in whole and in parts, and no one cares about it. (Except a few astro-geeks.) There isn’t anything to argue about here, although that doesn’t stop philosophers trying.

What people care about is the meaning of the cosmos as a whole—or the lack of it.

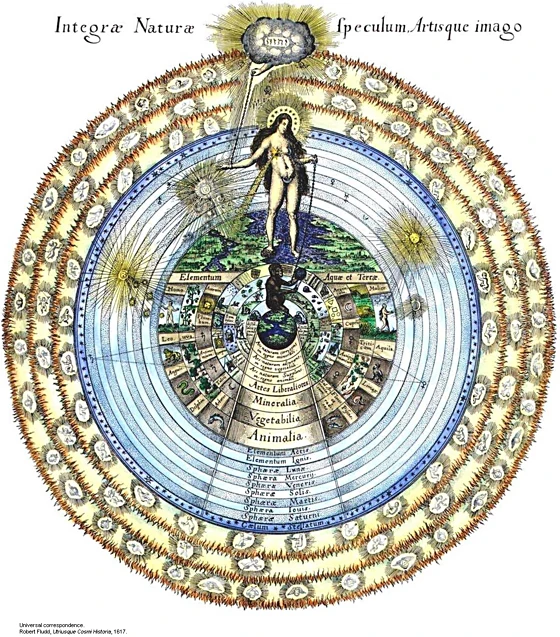

The Ancient Greek verb kosmein means “to put in good order,” and especially “to arrange troops in formation for battle” or “to establish a government.” Kosmos, then, is “that which has been ordered by command.”

Yahweh

After you were eaten by a cave bear at the end of the previous story, thirty thousand years passed. The magnificent arc of human progress ascended so far that chiefs could put into order arrays of tens of thousands of warriors, and command them into battle. They could slaughter whole cities to the last man, woman, and child, and streets ran with rivers of blood.

Sometimes this seemed quite unpleasant, and some people wondered if it was entirely necessary. Even some warriors secretly wondered whether following chiefs into battle was in their own best interest.

And so: Yahweh.

Originally, Yahweh was the war chief—but not the High King—of the vast Israeli pantheon.2 In perhaps the oldest tale in the Bible,3 Yahweh, speaking through his prophet Deborah, commanded the human Israeli war chief Barak to gather ten thousand spearsmen to fight against Sisera, an enemy war chief, who commanded a numerically and technologically superior force with nine hundred chariots of iron. Yahweh himself ordered ten thousand stars to descend with their spears of cold fire, and led them also into the battle. At Meggido—site also of Armageddon, the future battle at the end of the world—the combined human and divine armies defeated Sisera.

Six hundred years later,4 speaking through his priests, Yahweh abolished all the other gods, and commanded the primordial chaos into a cosmos, to His liking. He arrayed each and every thing in the world to order with His Word.5 It is true that His cosmos was only a few hundred miles across, an unimpressive effort by later standards, but that wasn’t the point. The point was that everything was rendered significant by the fixed purpose He gave it. Especially people, who he spent the rest of the Bible ordering around and smiting for disobedience. His priests and duly anointed kings saw that this was good.

Other warlike tribes got their own cosmoi, of course. I’m just doing Yahweh because half the fragments of cosmos the West retains are vestiges of His.

The cosmos

Around the same time, the arch-rationalist Greek philosopher Pythagoras used “kosmos” to refer to the heavens: the stars whose eternally regular motions were ordained in the cosmic plan of the eternal ordering principle. Pythagoras was an astro-geek, so he cared about things like that. Normal people don’t. Nevertheless, over-optimistically, others extended his term to the sublunar world of horse-armor, lamb-roasts and cosmetics—and, most importantly, themselves. That’s where we got the other half of our now-shattered cosmos.

The cosmos is the fixed order of the world humans live in, devised by God or something functionally equivalent,6 for a purpose in which humans play key roles. The cosmos gives everything in the material world a functional meaning, and also gives every human being a social meaning.

“The meaning of the cosmos as a whole” is the purpose served by the cosmic order. It has nothing to do with galaxies. Your personal purpose is a piece of the grand overall purpose, that fits together neatly into the rest. You are placed into your proper role in the cosmic battle array by divine command.

These are our cosmic meanings, the true meanings that really matter. They contrast with the trivial, illusory meanings we just make up, from our egocentric perspective, to satisfy base animal desires.

Or, so proponents of “cosmic meaning” would have you believe. As we’ll see later, misunderstanding “cosmos” as “universe” does make believing difficult, because galaxies are obviously meaningless. Then it is plausible that cosmic meaning doesn’t exist.

Nihilism takes the next step: nothing is meaningful at all, because it’s not cosmically meaningful.7 This is an instance of a common nihilistic reasoning error. It assumes meaning would have to work a particular way (cosmically, in this case); observes that it doesn’t; and concludes that it doesn’t exist.8

This nihilistic complaint gains credibility from the postmodern fragmentation of the social order. Social roles are no longer fixed by the cosmic plan. They are increasingly complex, uncertain, and nebulous. No one, neither chieftain nor god, can guarantee your significance nor purpose. You want to be part of something much greater than yourself, but there is no universally recognized social institution that can grant that.

You get choice; and with that, groundlessness. It’s a mixed blessing. To varying extents, everyone feels nostalgia for the traditional, natural human way of being: in a stable, significant role among a close-knit clan. That nostalgia can be exploited by malign ideologies bearing false promises; but it’s also genuine, and motivates much of the best of human activity.

How significant is enough?

The social meanings we can get now may seem not only nebulous, but not big enough. Nothing is significant enough to count: there is no cosmic meaning. The things you might be able to do are so tiny, compared with the cosmos. Getting galaxies mixed up with your thinking about social significance doesn’t make rational sense, but there are powerful underlying emotional intuitions connecting social and cosmic meanings.

If you will have to rely on the clan when cave hyenas attack, you must always wonder whether they will take that risk. Emotionally, the cosmos is an expanded, supernatural analog of the clan. Is it willing to protect you? Can you compel it to, if it’s acting sullen? In the prehistoric clan, these were questions about your social status and power.9

Repute

Remember “I get duped by eternalism in a casino”? I won thirty-seven cents in a slot machine, and:

I realized that the universe loved me, and that everything was going to come out well after all. My ever-present nagging sense of vague wrongness disappeared, and I recognized that it had always been a misunderstanding. Everything is as it should be; everything is connected; everything makes sense; everything is benevolently watched over by the eternal ordering principle.

This was eternalism straight-up, with no conceptual framework. God was not in the picture. Instead, I had just a vague feeling about my relationship with the Non-Me. When I say I felt that “the universe loves me,” this did not involve any concept of “the universe” as a thing; rather, a vague omnidirectional feeling of being loved.

I said “the universe,” but I meant the cosmos. Which, I suspect, was my brain somehow mistaking thirty seven cents for the unconditional enthusiastic support of my clan. “They keep giving me stuff, for nothing!” Except I come from a typical modern Western nuclear family, not a clan; its few members loved me, but were not going to be much help in a hyena crisis.

It’s important to stay on the right side of your clan, especially the more powerful members. In a clan, you are constantly doing each other favors, partly to gauge reactions, to test who will go how far to support you. Your status in the clan, your repute, how much you are liked, respected, or feared—your significance to the clan—is evolutionarily critical.

When Yahweh abstracted the clan into the cosmos, He promised absolute reliability. If something that big loved you, it wouldn’t stop capriciously when the chief’s nephew came to power, or due to some accidental loss of your social value, like a laming hyena bite.

In the modern West, we have to rely on vast anonymous societies. They too are capricious. How can we gauge their support?

Many people feel that they would have to do something spectacular in order to count as having a meaningful life. Finding a cure for cancer, or writing The Great American Novel, would make you special, and then life would be meaningful. Why? The unthought emotional logic: it would prove that you are valuable enough to society that everyone would feel compelled to help in case of hyenas. How can you check the level of compulsion? Fame. Famous people’s lives are meaningful; yours isn’t.10

But how famous do you need to be, for your life to count? Once you get on the fame treadmill, nothing seems ever to be enough. You could be “more famous than Jesus,” as the Beatles were half a century ago, and get mostly forgotten even before you’re dead.

Anyway, nobody in the Andromeda Galaxy was impressed with Beatles, not even in the 1960s. They weren’t cosmically significant. What would you have to do to get known there?

Power

Brief and powerless is Man’s life; on him and all his race the slow, sure doom falls pitiless and dark. Blind to good and evil, reckless of destruction, omnipotent matter rolls on its relentless way…

—Bertrand Russell, 190311

Meaning is causal. Nobody cares about you in Bangladesh, because you have no impact there.12 When the sales pitch transports you to the Andromeda Galaxy and tries to convince you that your earthly life is meaningless, it’s because you have no effect on the eldritch abominations living there.

What you need is power. You can’t rely on the clan unless you are are a powerful member. You can’t rely on it absolutely unless you have absolute power.

Some, hungry for meaning, say they want to “make a dent in the universe.” What’s up with that lust for cosmic vandalism? You need unlimited power to compel the entire universe. Some nihilist manifestos make it explicit: even that would be inadequate. Nothing short of personal Godhood could make your life meaningful. You need transcendent meaning, standing outside the universe altogether.

But the puny Biblical God could create only one, finite universe. Lame. Our universe is a tiny atom in the infinite sea of universes created by some Indian gods. Would having the power to create and destroy countless universes on a whim, for a joke, or in hope of impressing some goddess enough to get her pants off be enough power to count as meaningful? You can always take this nonsense a step further. What’s the threshold for significance?

Meaning is a tool. Do you throw your potato masher away because you can’t also mash galaxies with it?

There are already eight billion humans. As far as approximately eight billion of them are concerned, your life is insignificant. Galaxies’ opinions are irrelevant: either you are significant on the basis of your limited, local causal effects, or not at all. If you want to make a rational case for “not at all,” you’ll have to leave “cosmic meaninglessness” out. Unimpressed space monsters don’t add anything extra to the eight billion humans who don’t know you and don’t care.

Seek social significance in society

… not in the Andromeda Galaxy.

Feeling lonely and worthless is a common cause of nihilism. When stabilizing it seems attractive, exaggerating that feeling into cosmic loneliness and worthlessness, by ruminating on the vast cold dark emptiness of intergalactic space, can be effective.

When you’re fed up with nihilism, and become willing to work your way out of it, reluctantly reentering society may have to be part of the package. Finding an adequately significant social role is surprisingly satisfying, daunting as that task may seem at first.

You become significant by doing significant things, with other people. They don’t need to be cosmically significant. It’s actually OK to be less famous than Jesus and less impressive than God. You can start small.

It helps if you aren’t hostile, depressed, or superciliously intellectualoid. It helps if you are interesting. You become interesting by becoming interested in the world, and then doing stuff. The upcoming chapter on the complete stance explains how.

Astrology is rational

Not just rational: it was critical for the survival and evolutionary success of humans for hundreds of thousands of years.

Many plant and animal species have evolved a reproductive strategy called “predator satiation.” All the members of the species reproduce at the same time, producing so many offspring that predators cannot eat all of them. In plant species, all the fruits or seeds may come ripe within a couple days of each other, overwhelming the ability of animals to eat them all before some can find their way into the soil. Some animal species hatch or bear young all at the same time, for the same reason.

These species synchronize their reproduction to the annual solar cycle. Others migrate at specific times of year, either on account of annual weather patterns, or in pursuit of seasonal food sources.

In many regions, human hunter-gatherers migrated frequently too. They went to specific locations at specific times of year when they knew food would be abundant. In early autumn, they might go to the river where there’s a salmon run for a particular week every year, with more fish than anyone could possibly eat. A week later, they’d walk several days to the trail the bison take on their annual migration. They’d take a few calves from the vast herd, and spend the next week butchering and drying the meat to make jerky. Then they’d migrate to the bramble hill where blackberries were coming ripe. They’d have to keep an eye out for bears, but when the blackberries were gone the fattened-up bears would head to the same cave every year to hibernate. A brave hunting party might spear one in its sleep, and then the rendered bear fat, plus jerky and dried berries, would make the pemmican the clan needed to survive the snowy months.

It was essential to know when to migrate, within an error margin of only a few days. Nothing observable during daytime can tell you that. Fortunately, close observation of which stars appear on the horizon at sunrise and sunset provides an accurate calendar. Different constellations appear and disappear in the night sky according to the season.

Animals also behave differently according to the phase of the moon. Depending on how bright it is at night, predator and prey species—including humans, in both roles—are more or less vulnerable or active, according to which has better night vision. Some species time their reproduction according to the lunar cycle for this reason too. Nearly all cultures have believed that this is true of humans: surely it cannot be a coincidence that the human menstrual cycle has the same period?13

We live in an engineered world of manufactured objects that have objective properties. Our ancestors did not. Everything in their environment was irregular, nebulous—with the exception of a clear sky. The pattern of celestial motions recurred with absolute regularity, year after year, decade after decade, grandparents to grandchildren, the same since the Dream Time, eternally. That was the only objective truth available for nearly all human existence. Astrology—observing the effects of the night sky on the terrestrial world—was the most powerful, reliable, and rational method of prediction known for a million years. It’s probably in our genes14—and that is another part of what goes into “cosmic meaningfulness” today.

By the time of Yahweh, urban empires had kept written records for a thousand years and commanded order over regions a thousand miles across. That confirmed the universality and objectivity of astrology: the heavenly cycles are not a matter of opinion; they are invariant across vast expanses of time and space.

Probably this is where eternalism began. In the face of pervasive, chaotic discord, plague, famine, and war: “Why can’t our lives be predictable like the stars?” That made the heavenly bodies essential to the kosmos, the ordering of the world.

There was a niggling mystery: all the stars are fixed, except five, which the Greeks called planetoi, “wanderers.” Their motions seem mostly regular, but then sometimes they stop and go backwards for no apparent reason. Perhaps that could explain the remaining apparent randomness of terrestrial life?

Babylonian astro-geeks cracked the code. By mathematical analysis of centuries of precise observational data, they derived methods able to predict exactly when and how the five planets would misbehave, triggering epidemics, crop failures, and invasions. This was not only the source of the Biblical cosmos, but the model for all subsequent science.

Rationality destroyed the cosmos

You know the next part of this story. In Yahweh’s cosmos, the sun and stars went around the earth, by His command. Then: Copernicus. Galileo, eppur si muove. Darwin, Einstein, yadda yadda, all that stuff.

Science drained all the magic from the world. God got restricted to Sunday mornings, then died of neglect. His cosmos passed with Him. All that was left was the universe: mere atoms and the void. We were turned out of the Garden of Eden again: the fruit of the tree of knowledge alienated us from our natural abode. We were no longer at home in the world—because there no longer was any “world,” only a bleak, uncaring scattering of meaningless dead matter.

The death of the cosmos prompted the wrong idea that if there is not total pattern there must be total chaos. If the universe is uncreated, then it is random, meaningless, incomprehensible, and so must its parts be. This is where nihilism begins, in the failure of eternalism, at the end of world. And so then also existentialism: since the universe is meaningless and entirely random, any seeming meaning must be an arbitrary human imposition (“but maybe that’s sort of OK-ish, somehow”).

Influential political philosophers concluded that, with no cosmos to boss us around, social roles were indeed arbitrary impositions. Rationally, you must pursue your personal vision of meaning, unencumbered by archaic religious superstitions and oppressive hierarchies. You are a free individual, and can pursue your own chosen morality, with no particular responsibility to anyone. Clans were abolished by enlightened decree. Except in a few cases explicitly specified by rationally-conceived laws, no adult has any reason to support any other.

There’s much to like in our world of atomized individuals, but much of value that was intrinsic to our evolutionary heritage was rejected and forgotten. Our vague feeling that something important is missing, which we may sometimes articulate as “cosmic meaning,” refers in part to that.

The universe is too big

People have been complaining about this since Galileo blew the cosmos to bits in the early 1600s.

When I consider the short duration of my life, swallowed up in an eternity before and after, the little space I fill engulfed in the infinite immensity of spaces whereof I know nothing, and which know nothing of me, I am terrified. The eternal silence of these infinite spaces frightens me.

—Blaise Pascal, writing around then15

They’re still going on about it:

We are ephemeral beings on a tiny planet in one of hundreds of billions of galaxies in the universe (or perhaps the multiverse)—a cosmos that is coldly indifferent to the insignificant specks that we are. It is indifferent to our fortunes and misfortunes, to injustice, to our hopes, fears, values, and concerns.

—David Benatar, The Human Predicament: A Candid Guide to Life’s Biggest Questions, 2017

But why is the size of the universe a problem? We’ve already had one explanation: it provokes the evolved agoraphobia of early humans lost on an open plain, separated from the clan, and therefore vulnerable to cold, starvation, and predators.

“Too big” usually gets followed immediately by “knows nothing of me” or “is coldly indifferent.” This is the complaint that, unlike the cosmos, the universe cannot stand in place of the clan to provide social support and social significance. The stars of the cosmos were close enough to take a friendly interest in human affairs; the stars of the universe are not.

Distant galaxies are meaningless. So what? Specks of dust are meaningless, too. Is that a problem? No, so what makes galaxies different? Often, big things are more meaningful than little ones. If you take down a wooly mammoth, it will feed the clan for a month and everyone can stop worrying about hunger; but there’s not a lot of meat on a shrew. If the biggest things in the universe are meaningless, maybe that suggests everything smaller is too.

On the other hand, distant things are generally less meaningful than near ones. As you zoom out, more and more come into view, and you cannot care about them all. You have some maximum capacity for perceiving significance, and when you divide that by eight billion people, you get pretty nearly zero. Even more so if you divide by hundreds of billions of galaxies, each containing hundreds of billions of stars. On average, everything in the universe must be utterly insignificant, and what makes you so special?

This is silly, although philosophers have wasted careers arguing about it. Meaning is not evenly distributed through space.

Maybe the main upset is that the universe is too big to be a cosmos. Essentially all of it is meaningless, which makes it implausible that Yahweh created it as a home for human beings. And then, since His whole job was to run the cosmos, it becomes implausible that He even exists, or anyway that He’s going to grant us any significant meaning. If there’s no life elsewhere, it would have been extremely inefficient for Yahweh to have created so much universe for no reason, and He doesn’t seem that dumb. Alternatively, if we have to share His love with trillions of tentacle aliens in the Andromeda galaxy, He’s probably too busy to care much about us anymore.

A broader perspective

Caught up in the intricate concerns of your everyday life, you may not stop often enough to consider broader questions of meaning. If you step back from your immediate projects and problems, you may find an outside perspective a valuable way to shake yourself out of egocentric materialism. This view lets you see that some of your concerns may be less important than they seemed from up close. Also, it reveals that some life choices, which made sense at the time, were somewhat arbitrary in retrospect. It could be good to reconsider them.

Zoom out from your self a notch. At times your friends and family may seem not to care, but that is only because they are distracted with the web of meanings in their lives. As you see your own myopic self-concern more clearly from a step back, you realize that theirs is the same. You develop compassion for them, and for yourself, and can relax enough to give both space, and to act from empathic care more often.

If you find yourself socially isolated, you still nevertheless interact with other people occasionally. You have choices: even your tone of voice when checking out at the supermarket can make the world slightly better or worse. Sometimes something you say casually can make a disproportionate difference in someone else’s life. We all have meanings for others that we can never know.

Zoom out again. Let’s say you live in Berkeley, California. Hike up to Wildcat Peak, just outside town. You get a glorious perspective on all the neighborhoods and major roads and the university and the harbor. You’ve seen them all close up, but now you realize you hadn’t understood how they all fit together in the big picture. You can see south to Oakland, with the cranes in its port that inspired the giant war robot walkers in Star Wars,16 and the Bay Bridge, and San Francisco across the Bay, and the Golden Gate connecting to Marin and Mount Tamalpais.

Looking out from Wildcat Peak, you feel a million people living their lives, even if you cannot see them individually. Those lives include enjoyable and useful and meaningful activities—along with much suffering and pointless tedium. This distant overview of their lives can give you greater objectivity on your own, by analogy. That allows a judgement more like that of a neutral tribunal. It can increase the scope of your motivations. You may decide to become part of a purposeful group project that is more significant than your personal concerns.

The view from afar is not inherently more accurate. It is less so, in fact, because it loses detail, which you can fill in only with imagination. From Wildcat Peak, you can see all the way to the South Bay, but it’s too far to see clearly; just a lumpy gray blur. The value of perspective is that it is a different and complementary view on your life, not that it is a better one. It’s not useful to take only this view.

Zoom out. If you are reading this, you probably live in a country that, despite infuriating exceptions and appalling mistakes, provides far greater security and support to most people than your Paleolithic clan, or an Iron Age empire in the era of Yahweh, ever could. Life has gotten spectacularly better on average, socially and culturally as well as materially. On the whole, on average, we have good intentions, and can reasonably expect to create a better future together. Each of us, including you, can contribute to that in some small way.

Zoom out. Astronauts who have seen the whole earth from space describe it as astonishingly beautiful, far more so than they had expected. Many find this perspective a profoundly meaningful experience, of connection and grace.

Apollo 14 astronaut Edgar Mitchell said:

You develop an instant global consciousness, a people orientation, an intense dissatisfaction with the state of the world, and a compulsion to do something about it. From out there on the moon, international politics looks so petty. You want to grab a politician by the scruff of the neck and drag him a quarter of a million miles out and say, “Look at that, you son of a bitch.”

There was a startling recognition that the nature of the universe was not as I had been taught… I not only saw the connectedness, I felt it.… I was overwhelmed with the sensation of physically and mentally extending out into the cosmos. I realized that this was a biological response of my brain attempting to reorganize and give meaning to information about the wonderful and awesome processes that I was privileged to view.

One with the cosmos

Centuries after Galileo killed it, the scientist Alexander von Humboldt resurrected the cosmos in the mid-1800s. He revived both the word “cosmos,” barely used in the interim, and the concept.

Humboldt promoted Romanticism, the mainstream intellectual movement of his era. Romanticism rejected objectivity in favor of the subjectivity of strong emotions and aesthetic appreciation, especially of nature. It repudiated the Enlightenment’s reductive, mechanistic rationalism. It championed instead a holistic understanding of the cosmos as a single, intricately interconnected, organic and spiritual entity, pervaded with a subtle life force. For Humboldt and Romanticism, the scientist does not stand apart from and above the material world, regarding it with detached contempt; but is an integral part of Nature, not separate from it, and should regard it with love, worship, and awe.

Humboldt’s book Kosmos influenced generations of thinkers. Richard Maurice Bucke popularized the term “cosmic consciousness” after a mystical experience in 1872:

All at once, without warning of any kind, I found myself wrapped around as it were by a flame-coloured cloud. For an instant I thought of fire, some sudden conflagration in the great city; the next, I knew that the light was within me.

Directly afterward came upon me a sense of exultation, of immense joyousness accompanied by an intellectual illumination quite impossible to describe. Into my brain streamed one momentary lightning-flash of the Divine Splendor which has ever since lightened my life; upon my heart fell one drop of Divine Bliss, leaving thenceforward for always an aftertaste of heaven.

I saw and knew that the Cosmos is not dead matter but a living Presence, that the soul of man is immortal, that the universe is so built and ordered that without any peradventure all things work together for the good of each and all, that the foundation principle of the world is what we call love, and that the happiness of everyone in the long run is absolutely certain.17

If this sounds more like 1972 than 1872, that is no coincidence. The anti-rational New Age counterculture wasn’t new at all. Nearly all its ideas were lifted directly from the Romantic era. The oftimes mindless hippie exclamation “wow, cosmic, man!” is straight out of Humboldt.

This monist-eternalist vision is mainly factually mistaken and spiritually harmful. However, even now it may be a useful corrective to nihilist-dualist, reductive rationalist misunderstandings.

If you scorn “cosmic meaningfulness” but secretly feel some wistful regret that it does not exist—I will suggest that you may be able to find it after all.

Yoshimi Battles The Pink Robots

—Wayne Coyne, the songwriter and singer of this album, explaining it

I was driving due south late at night on SR1, the main New Zealand highway, with the Flaming Lips’ Yoshimi Battles The Pink Robots on the CD. It was 2002, long sections of SR1 across empty parts of the country were still unpaved, CDs were still a thing, and the album had just come out. I’d bought it in Auckland for the drive, on the recommendation of a review that said it sounded like no previous music, and featured Wayne Coyne “wittering on about the meaning of life.”

It was a moonless night and I couldn’t drive fast on the gravel road and I couldn’t see anything much so I was looking mostly at the starry sky. The Milky Way was dead ahead, and exceptionally bright. I was in the middle of nowhere, so there were no city lights and the sky was clear. Clear except two small clouds, far off, many miles away to the south, off a bit to the side of the Milky Way.

Half an hour later I noticed they were still far off, many miles away to the south. They were glowing, as clouds sometimes do when they reflect moonlight. But there was no moonlight. I watched as miles of empty darkness rolled by and they got no bigger.

Yoshimi Battles The Pink Robots is a sad, spooky science fiction album about the end of the world, and it was late at night, and I was starting to get spooked.

The only theory I could come up was that the clouds were glowing remnants of nuclear explosions, much further in the distance than I had supposed.

Had I missed the beginning of Armageddon? Would anyone even bother to nuke Wellington, my destination, the capital of New Zealand? It seemed extremely unlikely, but I pulled over and got out of the car, wondering tensely whether it was sensible to take the risk of continuing to drive toward what even might possibly be a radioactive conflagration in the city.

Slowly, as I shivered and peered south, a better explanation assembled itself.

Antonio Pigafetta was the proto-scientist on Magellan’s disastrous 1519–1522 expedition, the first circumnavigation of the planet. In his account of the voyage, Pigafetta reported that near the Antarctic pole of the sky “there are many small stars congregated together, which are like to two clouds a little separated from one another, and a little dimmed.” Later they were named the Magellanic Clouds.

Could it be? I had read about the Clouds as a teenager, but had not seen a picture, and it never occurred to me that I might also someday see them. They are the two galaxies closest to the Milky Way, although further than the tens of miles down the road I had imagined. Just about one quadrillion miles further. They are the largest, most distant things you are likely ever to see without a telescope.18

My fear turned to wonder, and awe, and elation in the face of vastness. Miraculously, individual photons had spent hundreds of thousands of years traveling across nothingness just to fall into my eyes, thousands every second, so I could see that the Clouds were part of my world, and I was part of their world, and we were both held by the universe.

Turns out… galaxies can be meaningful after all.

Image (CC) ESO/C. Malin

Vastness

Whether contemptuous or wistful, the claim that nothing is cosmically meaningful expresses a feeling of loss at being cut off from vastness.

The emotional root of nihilism is the sense, usually accurate, that some important aspect of meaning is missing from your life. Sometimes that’s a normal, explainable, ordinary sort of meaning: nothing seems to have any purpose, for example. Sometimes the lack is obscure, or even unnameable. Vastness is one form of such non-ordinary meaning.

We have three emotional responses to vastness. It can provoke terror, as it did in the great philosopher Blaise Pascal four hundred years ago. It can engender curiosity, wonder, and awe at its beauty, as many astronauts report. We may not get a choice between these two, because the experience can be overwhelmingly intense. When that is too emotionally difficult, we may nihilize it, more or less successfully. That is, we may try to un-see vastness, or to deny its meaningfulness.

Alternatively, if it seems worth the risk, you can deliberately pursue vastness, for the perspective it gives on meaning, and for the possibility of personal transformation. (There’s more about this in the complete stance chapter, starting in the page on wonder.)

There are several routes to vastness. One of the most reliable is to seek it alone in nature. It may be found in the sky, night or day; in the ocean; or in mountains. Although I’m a bit of an astro-geek, I find the last of those most effective myself. I wrote about this in “At the Mountains of Meaningness.”

But you might locate vastness anywhere on a clear night far from civilization.

I found myself in a tiny one-man tent, sheltering from a violent thunderstorm in the remote mountains of Mexico. When the rain finally stopped, I squeezed out into the night. I felt anxious and alone until I looked up, and was hit by a rush of adrenaline. Above me was a radiant, shimmering sea; an ocean of light that stretched not just from horizon to horizon but deep into forever. For a brief moment, I was lifted up, connected, home.

Thinking back, it isn’t the individual constellations I remember, or the planets, or even the glittering ribbon of the Milky Way. It is simply the sheer awesome power of the sky. In London, where I live, the night sky is dull and dark with a neon orange glow, its emptiness broken by only a few struggling pinpricks of light. But here the veil was lifted, as if returning to me something that I hadn’t even known was lost. On this moonless night, it seemed there was no blackness at all. There was only silver. Only stars.

—Jo Marchant19

- 1.I read several dozen academic papers on cosmic meaninglessness. I found them generally tedious and silly. I have two reluctant recommendations if you want to read some anyway. First, Iddo Landau’s “The Meaning of Life Sub Specie Aeternitatis,” Australasian Journal of Philosophy 89:4, (2011). His treatment is generally sensible and concludes that life is not meaningless even when viewed in an intergalactic context. Second, Guy Kahane’s “Our Cosmic Insignificance,” Noûs, 48:4 (2014) pp. 745–772. If you accept the mistaken premises that “cosmic” means “in terms of the physical universe” and that significance is sufficiently quantitative to enable arithmetical division, his paper is well thought through—whereas most others contain glaring logical errors as well. Both papers are fairly recent and summarize the prior literature, which you can definitely skip.

- 2.This is discussed in the standard work on the gradual development of Israeli religion from Canaanite polytheism, Mark S. Smith’s The Early History of God: Yahweh and the Other Deities in Ancient Israel. Naturally, this analysis is not accepted by all people of the Book.

- 3.Judges 4–5.

- 4.Historians date Judges 4–5 to the twelfth century B.C.; monotheism and Genesis to the sixth.

- 5.The Genesis creation myths are revised versions of earlier Mesopotamian ones. In those, the material world already existed before the gods commanded it into order as a cosmos. Genesis 1 can be read that way also. The verb typically translated there as “created” also means “commanded its functional role,” and the Genesis scholar John H. Walton suggests that that this is the correct reading in context. See his Genesis: The NIV Application Commentary, or a summary at “Material or Function in Genesis 1? John Walton Responds,” BioLogos, April 3, 2015.

- 6.“Anaxagoras, born about 500 BC, is the first person who is definitely known to have explained the concept of a nous (mind), which arranged all other things in the cosmos in their proper order, started them in a rotating motion, and continuing to control them to some extent, having an especially strong connection with living things.”—Wikipedia, s.v. Nous.

- 7.Or not meaningful enough to count, in the case of lite nihilism.

- 8.Donald Crosby’s The Specter of the Absurd: Sources and Criticisms of Modern Nihilism, p. 128, has a nice analysis of this false, forced binary choice. “Everything in the universe must focus mainly on us and the problems and prospects of our personal existence, or else the universe is meaningless and our lives are drained of purpose…. When we find that there is much about the experienced world which does not fit neatly within any particular human scheme of interpretation, or that the world is perhaps not as wholly subordinated to our purposes and needs as we had formerly thought, then we despair.”

- 9.Guy Kahane makes the same suggestion in passing: “It would be amusing if the desire for grand cosmic significance is ultimately just the projection of the evolved concern with status that we share with other primates.” See also Robin Hanson’s blog post “Meaning of Meaning of Life,” Overcoming Bias, September 7, 2010.

- 10.Social media provide a simulacrum. If you had a million followers on Instagram, that would make your life meaningful, right? You’d really be someone then.

- 11.Bertrand Russell, “The Free Man’s Worship,” The Independent Review 1 (Dec 1903), 415-24

- 12.If you are famous in Bangladesh, substitute Belgium or Botswana or Betelgeuse.

- 13.Although nearly all cultures consider it highly significant that the menstrual cycle accords with the lunar one, it appears that they are mistaken; current science finds no synchronization with the moon, nor even between women.

- 14.I have no specific evidence for this hypothesis. Attributing great meaningfulness to the stars is a cultural universal, but maybe that’s just because our ancestors spent hours looking at the sky every night. Before there were roofs and candles, there wasn’t much else to do.

- 15.From Blaise Pascal’s Pensées, a collection of notes published posthumously, so it’s not known exactly when he wrote this. Many other people were rendered similarly upset by the early-1600s astronomical discoveries that demolished the Medieval cosmology.

- 16.George Lucas denies that he based the AT-AT walkers in The Empire Strikes Back on the Oakland cranes, but if you see them it’s obviously true, as everyone who lives around there knows; so who cares what he thinks.

- 17.Paraphrased from Bucke’s Cosmic Consciousness: A Study in the Evolution of the Human Mind.

- 18.The Andromeda Galaxy is bigger and further; under ideal conditions, it is barely visible to the naked eye as a vague faint smear. The Milky Way is bigger than the Clouds, but it’s closer, and you can’t see it as a single thing. We’re inside it, so it appears as a broad nebulous band of random weird stuff that always continues below the horizons.

- 19.Jo Marchant, The Human Cosmos: Civilization and the Stars, 2020. I came across this book half way through writing “No cosmic meaning,” and found it fascinating and inspiring. I’ve taken some details of my discussion from it. I can’t recommend it completely unreservedly, because it gets cozier with monist pseudoscience than I’m comfortable with. If you discount those bits, it’s wonderful.